In graduate school, I had the luck of landing an incredibly formative internship at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. At the time, Anna Walker was their Windgate Foundation Assistant Curator in Decorative Arts, Craft, and Design. I learned so much from working with Anna, and in many ways, that summer solidified my interest in the political potential of craft.

I remember collaborating with Anna on the show “Mending: Craft and Community,” in part organized around a recent acquisition, Tanya Aguiñiga’s Mend. I loved researching and discussing each and every work on the checklist, and I have fond memories of Anna’s excitement about another new acquisition that would be highlighted: Aaron McIntosh’s Freshman Magazine, August 2002 Issue (Broken Links). A few years later, the museum would spotlight this work in a virtual lecture.

I immediately felt drawn to Freshman Magazine’s remixing of imagery from an American gay pornographic magazine through the soft-yet-sculptural, ultra-charged-and-intimate form of a quilt. I also marveled at the ways in which the circular patterning referenced but metamorphosed a traditional quilt pattern known as “lover’s links.” I’d soon learn that Aaron McIntosh’s artistic practice builds upon his experience as a queer fourth-generation quiltmaker growing up in Appalachia.

Imagine my surprise and thrill upon hearing that Aaron McIntosh was slated to open “Entanglements,” a solo exhibition at Northeastern’s Gallery 360 curated by Juliana Barton. This exquisite show ran from June 27 through October 21, 2023, and the virtual tour remains online. I reached out to the artist to learn more. The following conversation has been edited and condensed.

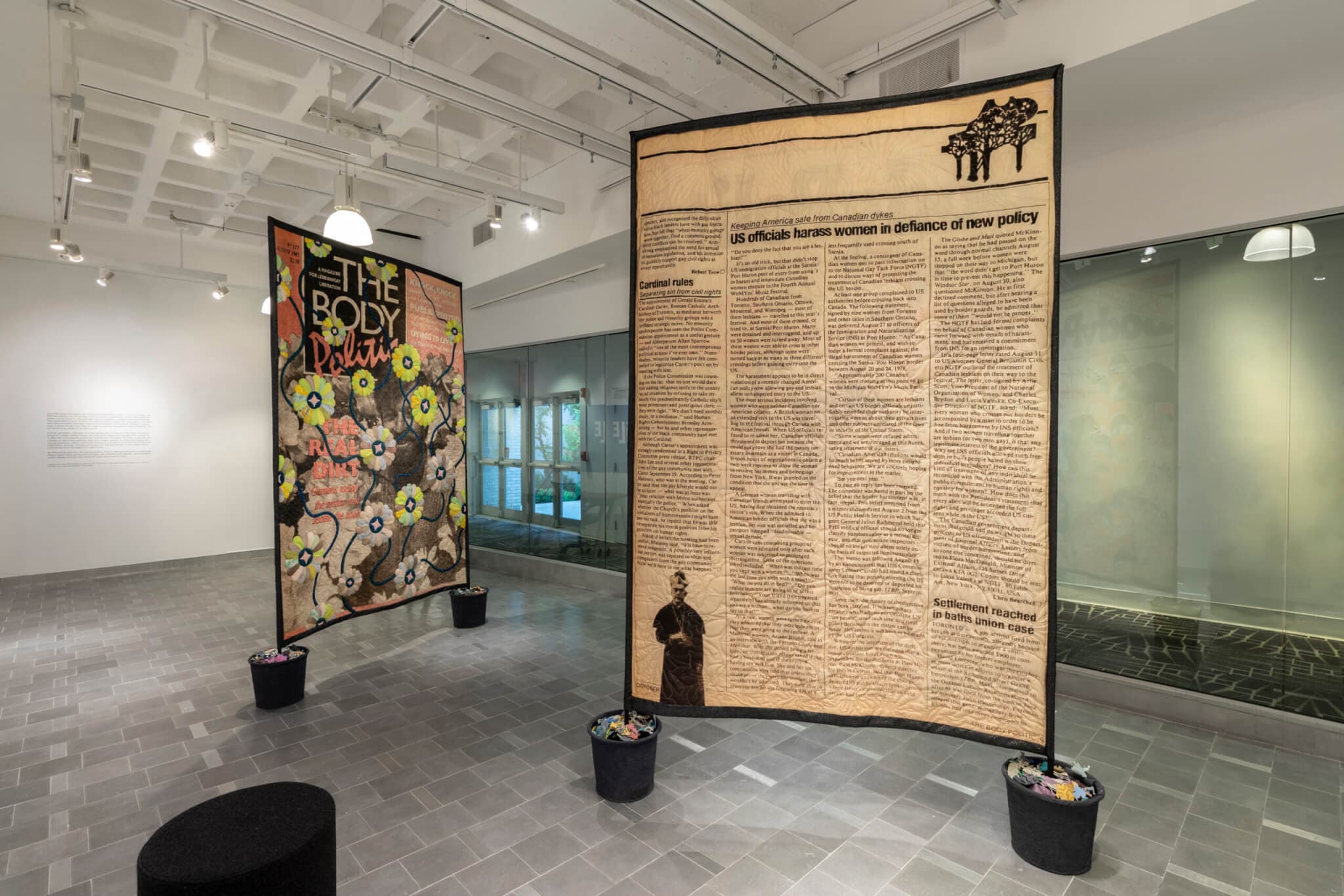

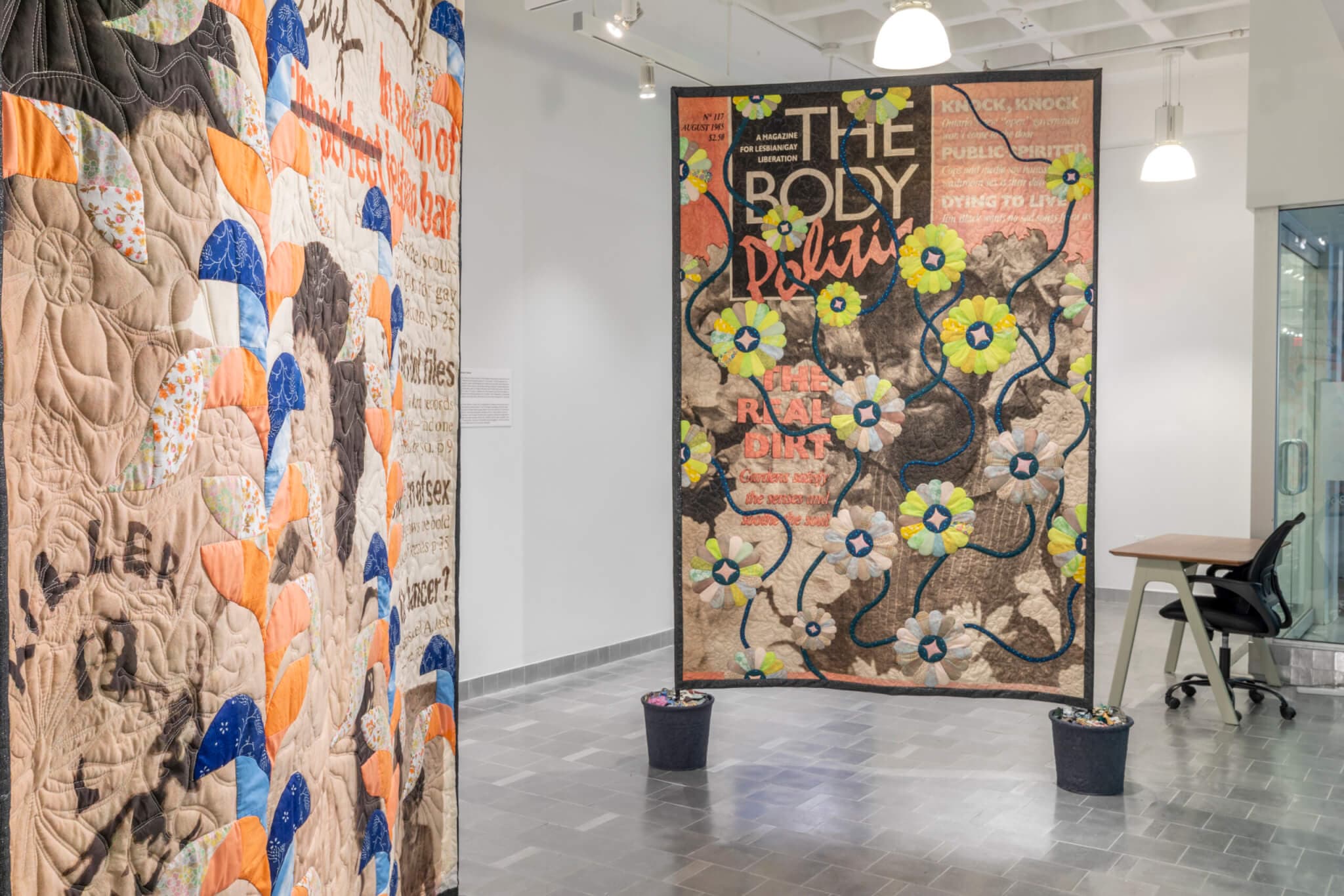

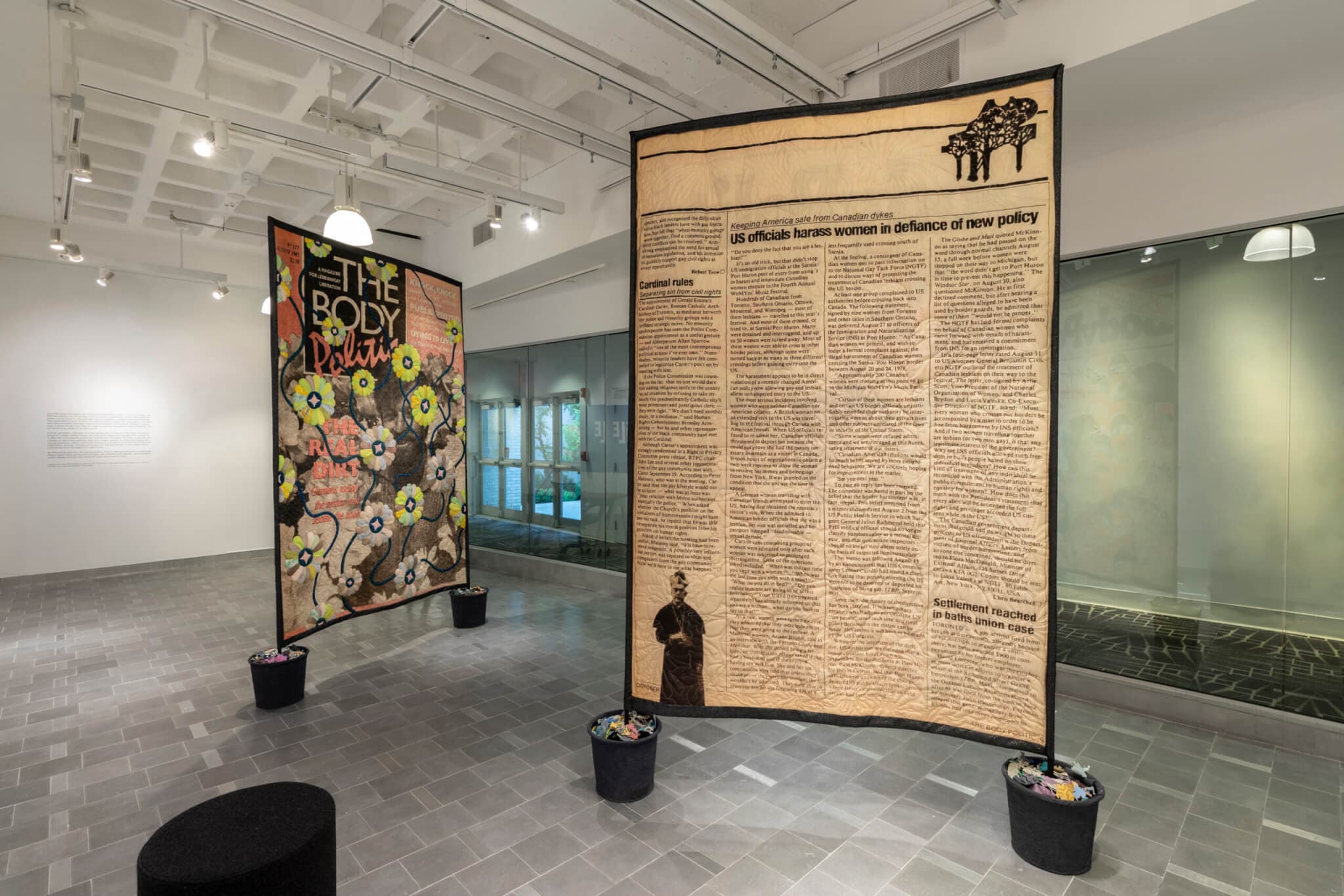

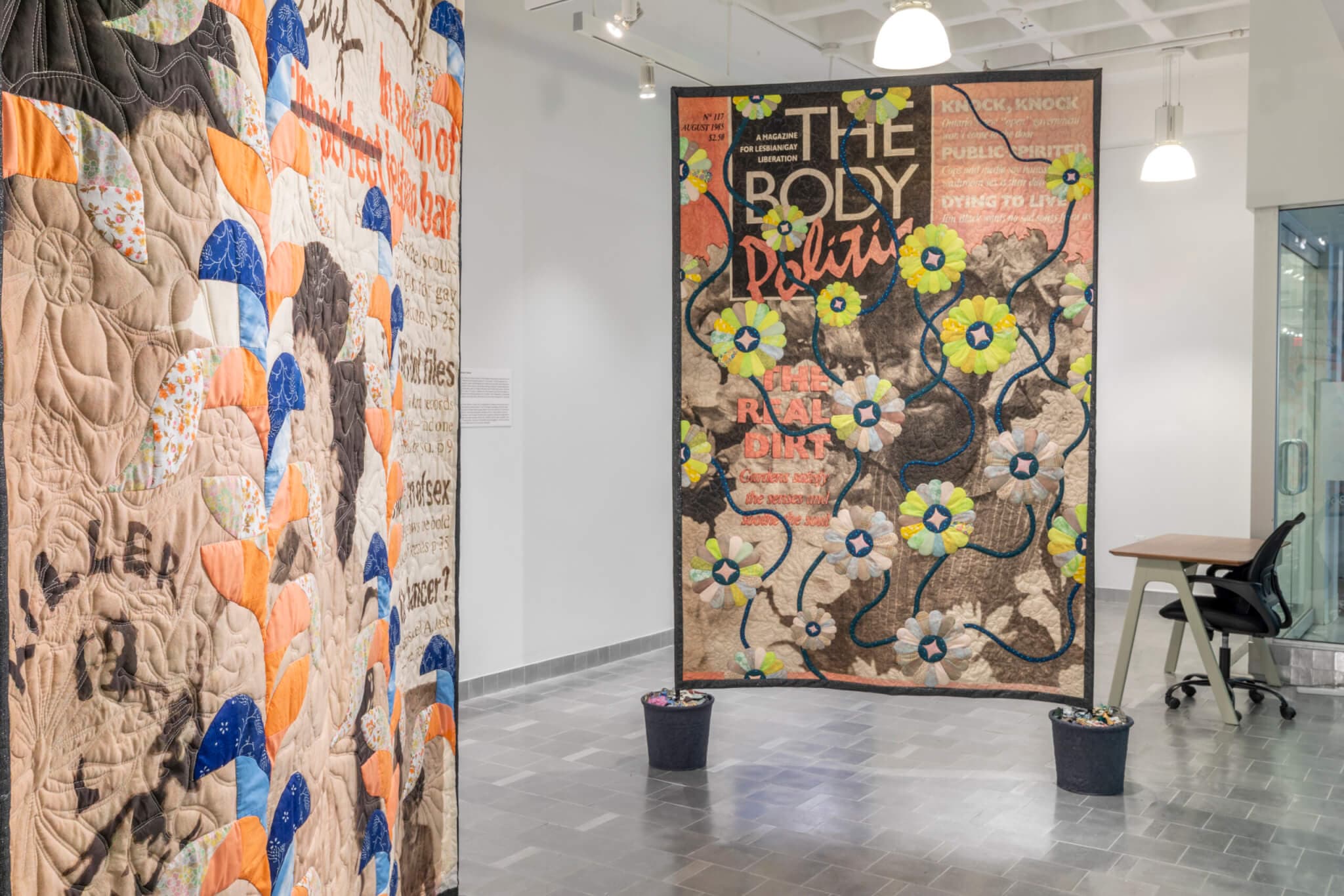

Installation view of “Entanglements” at Northeastern University’s Gallery 360, Boston, 2023. (left) Aaron McIntosh, Entanglements: Dying to Live / The Real Dirt, 2023. Digital textile print on muslin, vintage fabrics, thread. (right) Aaron McIntosh, Flowers at the Border / Keeping Safe, 2022. Digital textile print on muslin, vintage fabrics, thread. Courtesy of the artist. Photo by Mel Taing.

Kendall DeBoer: I’ll ask you about your exhibition at Northeastern’s Gallery 360 in a moment, but first I’d like to ask about your work in general. Would you share a bit about yourself and your practice?

Aaron McIntosh: I’m a fourth-generation quilt-maker and a contemporary artist. I think of quiltmaking—work with scraps and piecework—as a global paradigm for identity formation. I think of it as a platform, a language. Some of my bigger concerns are heightening queer visibility and then also responding to its dangers and pitfalls, especially coming from a rural background and from a conservative religious family.

I’ve been interested in how we come to know ourselves, and for me, this queer body, through a host of other sources and media that are not necessarily from “popular culture.” As someone who didn’t have a lot of gay or queer pop cultural references in childhood, I arrived at knowing myself sexually through a variety of other influences: gay erotica, gay romance novels, pornography. I bring a lot of that to the work.

KD: I really liked how you describe the act of quilting and piecework not only as a material process but also as a lens for understanding identity formation. When did you start quilting, and was there ever any resistance to following your lineage as a fourth-generation quiltmaker?

AM: Textiles have so much potential for subversion. There’s a very palpable politics embedded in them: the resourcefulness of making something beautiful or utilitarian out of the refuse of one’s environment. I think I acquired quilting skills just by being around quilters. Nobody sat down and said, “This is how you do this.” I’d see my mom with her sewing machine, and my paternal grandma Axie was very involved in hand stitching and lapwork. Some of my earliest memories are sitting with her, playing with the needles and stuff like that. When I went to art school, I thought I might want to go into painting, but I also thought I might go into fashion. I discovered the fiber arts program and was like “Oh, this is the in-between.”

I had many positive relationships with fibers as a young boy. On my mom’s side, there were older generations of men who had also quilted, so I didn’t grow up with it being perceived as a gendered thing. No one ever told me I shouldn’t do it. I feel lucky as a queer person from my family to have not been turned away from that in a homophobic gesture or anything.

Installation view of “Entanglements” at Northeastern University’s Gallery 360, Boston, 2023. Aaron McIntosh, Invasive Queer Kudzu, 2015–ongoing. Mixed-media sculpture and queer kudzu vines. Courtesy of the artist. Photo by Mel Taing.

KD: I also wanted to talk about “Entanglements” and the overlapping types of works on view. A sizable portion is dedicated to your Queer Kudzu project and Monument Invasion series. Growing up in Houston, I remember the presence of kudzu and the negative language surrounding it, but you’ve reframed “the vine that ate the South” as something generative.

AM: In 2013, my grandmother passed away, and in the weeks leading up to her death, my mom and her sisters were tending her final garden. I’m out there with them and we’re pulling all these weeds. It was super awkward to be there. I had a partner for five years and my family didn’t feel comfortable with that person being around. I’m very tied to my family, and I love them, and yet it’s challenging. So I have this revelation in the garden about “Wow, I’m a weed. I’m like these weeds, doing their own thing.” They’re usually native plants and they grow really well at the margins, and I felt that was a quite nice metaphor for me.

I started making weeds out of things that have made me, and they’re informed by an infusion of family material—scraps from quilts, crocheted blankets, and romance novels, queer porn and erotica, and gay novels. The resulting sculptures became an amalgam of all those things. Making work about weeds, specifically in relation to the South, I felt I had to take on kudzu.

When I first showed kudzu in Baltimore, I had some friends suggest that I amp up the project to really take on the maximal invasion that is kudzu. I had already been doing cursory work in queer archives and I thought, maybe kudzu is a good place to think about queer archives in the South. As I spent time in the archives, I was struck by the omissions and misrepresentations, especially of non-normative gender and queer southerners of color. What would it mean to keep doing this project, and shift it to the stories of the present day? I launched it officially as a participatory and archive-based community art project in 2015.

Kudzu is famous for blanketing over an environment and obstructing structures like barns, farmhouses and telephone poles. I knew I wanted to use it to invade other kinds of structures, especially difficult and problematic things in the South that have kept queer people from advancing socially, culturally, and materially—and also look at the intersectional struggles of BIPOC folks and immigrants in the South.

Far from invading, kudzu was actually brought to the South with a lot of intention. Seven million seedlings were planted between the 1930s and 1970s across the South by the USDA, who thought it would be the next wonder crop, similar to the soybean. It didn’t behave in a marketable agricultural way, but was quickly adapted for erosion control, alongside new highway systems and train tracks. You usually see it from a car window, in places that are part of a landscape already changed by human presence. But it became the poster child of the Invasive Species Act, and it’s taken on this xenophobic, extremely othered identity in how southerners describe it.

I’m looking to flip that paradigm and think about kudzu as an exponential grower and an extremely useful plant. Kudzu has been part of the Chinese pharmacopoeia for 2,000 years, it’s a viable fiber for basket making, and people make jelly out of the blossoms. This is a project about asking bigger ecological and interspecies questions about our relationship with this one vine, which then also works as a metaphor for queerness in the South. I was trying to grow, sprout, and entangle queerness and queer communities across the South, especially because there are so many continuing challenges to organizing interstate or regional connections. It’s reflective, speculative work imagining a future for the South with less of the racist monuments and homophobic institutions.

(left) Aaron McIntosh, Monument Invasion: Jefferson Davis Monument, 2018. Collage on archival inkjet print. (right) Aaron McIntosh. Monument Invasion: Alabama State Capital Building (Former Confederate Capital), 2018. Collage on archival inkjet print. Courtesy of the artist. Photo by Aaron McIntosh.

KD: You’re referencing something I was curious about regarding the two Monument Invasion works in the exhibition. One is titled First Southern Baptist Church, and the other is MountainTop Removal, and both are from 2018. Are the archival leaves of the kudzu created in the same space by individuals from local communities in proximity to these titles, or are they from a national reach of different participants then brought into conversation with the specific place?

AM: So what you’re seeing in Gallery 360 is actually a selection of the 7,200-plus story leaves from many of the places that the project had visited between 2015 and 2020. When I was organizing the show with Juliana Rowen Barton, I wanted to bring as much of a cross section as I could. I have a lot of leaves from Houston, Baltimore, and Richmond but also from smaller communities in the Appalachian South.

The Monument Invasion collages were actually a way of me thinking through how these vines should be exhibited. There are five different sites that have specific significance to queer and regional struggles that affect not only 2SLGBTQ+ people. Mountaintop removal in particular has just decimated Appalachian former mining communities. From the ecological and environmental standpoint, there are entire generations of people that can’t live in that region anymore. First Southern Baptist Church has dual legacies. It’s where Southern Baptists broke away from the national Baptist church to uphold slavery, forming the Southern Baptist Convention. So it’s related to Civil War history, Southern separatism, and white supremacy. This church and many others in this denomination have held numerous anti-abortion and anti-same-sex-marriage protests over the years. The Southern Baptist Convention became a far-right Christian movement that, among many inhumane policy proposals, has been really suppressive of a lot of queer issues. We see this happening right now with all the transphobic legislation.

Aaron McIntosh, Invasive Queer Kudzu (detail), 2015–ongoing. Mixed-media sculpture and queer kudzu vines. Courtesy of the artist. Photo by Mel Taing.

KD: I want to ask about the archival aspect of your work. There’s always the question of how one shares archives in a way that’s accessible but also long lasting. Does one digitize them or gather oral history components? With your leaves, which are physical objects, are there any primary zones for sharing them beyond physical exhibition spaces or plans for that kind of thing?

AM: I would say the website and Instagram are the main ways the project is shared. My role as a steward of queer stories comes into play. Some of the things that people share at the community workshops are super sensitive, and it’s never been a project where I will digitize every single leaf and every single story. Many of them are anonymized.

The project will eventually be a part of multiple archives, not all in one location. That’s the goal. I’m excited about that future part of it. Accessibility of archives was always a goal for the project, which is in a small way to help bridge the gaps between older generations and younger queers, which have become so glaring and challenging. The project is a tangible way to actually show participants archive images on kudzu leaves, something that they could touch and could have a different relationship to than photos on a screen, or something that you need to make an appointment for months in advance and travel to. Sharing queer history with southerners across the South is an important solidarity-building aspect. And I like that it’s always stories from the past and stories from the present commingling in this kudzu vine. Things are in a constant state of living, dying, and being together, side by side.

Installation view of “Entanglements” at Northeastern University’s Gallery 360, Boston, 2023. (left) Aaron McIntosh, Flowers at the Border / Keeping Safe, 2022. Digital textile print on muslin, vintage fabrics, thread. (right) Aaron McIntosh, Entanglements: Dying to Live / The Real Dirt, 2023. Digital textile print on muslin, vintage fabrics, thread. Courtesy of the artist. Photo by Mel Taing.

KD: That intersectional and interconnected approach is apparent throughout your work. It’s always about not only sexuality, but gender, race, class, age, and even species. And I think that that’s something that using the botanical lens or non-human lens is useful for conceptualizing.

Your archival interests also appear in your large-scale quilt sculptures Entanglements: Dying to Live / The Real Dirt and Entanglements: Flowers at the Border / Keeping Safe, which display covers from a Canadian queer activist magazine, Body Politic. These works are collaborative in the sense that you’re working with materials put together by other people across space and time. And magazine covers have shown up in your quilts for years. Could you share a little about this?

AM: Finding a source way after the date of its publication really resonates with me; it’s like finding a portal transporting me back and forth between the past and present, and this helps me understand identity differently. It might be a snippet of a cultural moment. Or a gay erotica chapbook from the nineties, from a younger period of my life, or it might be a newsletter from the seventies. The Body Politic works are my attempt to understand Canada’s queer archives a bit better while living in a new country at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. One of the first things that struck me is the relationship between Canada and the United States in terms of 2SLGBTQ+ rights struggles.

The first one that I made [Flowers at the Border / Keeping Safe] was finished in 2022. The front and back sides feature a story about lesbians crossing the border to go to the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival and who were turned away on either side for “gross indecency,” or essentially for being queer. Section 159 of the Criminal Code is technically still enforceable to this day at the border.

KD: I love this beautiful and poetic description of the magical moment of finding echoes and resonances in the archive. These images are already powerful, but what does the act of transforming something from a magazine cover or a photo or a news story into the large soft sculptural scale of the quilt do?

AM: Well, it touches on something you asked earlier, which is a bigger question about archives: what they are, how are they accessible, how are they not? I’m very interested in images themselves, and what do images want? I think sometimes images might call out to you, let out a siren call to be something beyond paper. To transpose these images—which are often lost to time and are not very accessible—into something large and monumental creates a different orientation to queer history. These are not just small photos, languishing and archived somewhere; they’re something that I bring into contemporary art practice. They’re called “entanglements” because they use traditional quilt botanic patterns to wrangle, overtake, or tangle these images.

I’m also thinking of this entanglement between traditional craft practice and contemporary queer concerns. The quilt that features two lesbians includes a vining kind of patchwork—that’s a pattern I grew up around. The fabric is stuff that I have inherited over all these generations of people passing on. There’s an actual physical materiality of my existence entangling with these images and these queer histories. If you look kind of micro at some of the floral prints on the family cloth, that is what is magnified and done for the quilting. I imagine someone from my family, or maybe even a queer ancestor I would’ve never known, who’s sleeping or fucking under a quilt in the nineteenth century. The object itself is benign and of its culture, but maybe there are things that the quilt knows that the rest of the culture doesn’t know. I’m curious to push quilting out of its more comfortable niches with “Americana.”

Installation view of “Entanglements” at Northeastern University’s Gallery 360, Boston, 2023.

KD: I noticed in the exhibition there are two references to historical quilt making practices—traditional album quilts, and then also the AIDS Memorial Quilt. Do you see your work in relation to these historic moments?

AM: Everything I do is very invested in research and in scaffolding off of the work of people who came before me as a way of connecting with my various lineages. The AIDS quilt has been a formative presence in the Queer Kudzu project since the beginning, for sure. My work had never been shown in direct relationship to community projects like the AIDS quilt or other traditional quilts that have perhaps a relationship to social justice or activism until a 2020 exhibition at the Toledo Museum of Art called “Radical Tradition: American Quilts and Social Change.”

At Northeastern, Juliana had asked if there could be a community component. This grew out of a longer conversation in which I explained that the Queer Kudzu workshops only ever happened in the South. This is really a project for queer Southern stories, so it does not make sense to do that in Boston. I had a really positive experience working with the Chautauqua Institution last summer of doing an album-style quilt with them and for their community as a way of talking about quilts and social practice. So we developed this one for Northeastern.

It was really lovely to work with Juliana, who did a lot of independent research to bring to the fore a lot of other historic connections. We included a small library, which provides extra reading on quilt histories, critical botany, and queer ecological ideas that these recent projects have been built on.

KD: Is there anything you want to share with Boston audiences who haven’t seen your show or have seen your show?

AM: One thing I would say is that I’m excited for the show’s proximity to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. They have an incredible quilt collection, and Boston has been known throughout the years to have these large-scale, amazing quilt exhibitions. I don’t think I reinvented any quilt wheels, but I’m looking at the sculptural possibilities for the quilt, drawing from nature the way that kudzu blankets a landscape. I’m thinking about the quilts’ relationship to ideas beyond the bedroom.

Visit Northeastern University’s Gallery 360 online for a virtual tour of “Entanglements.”