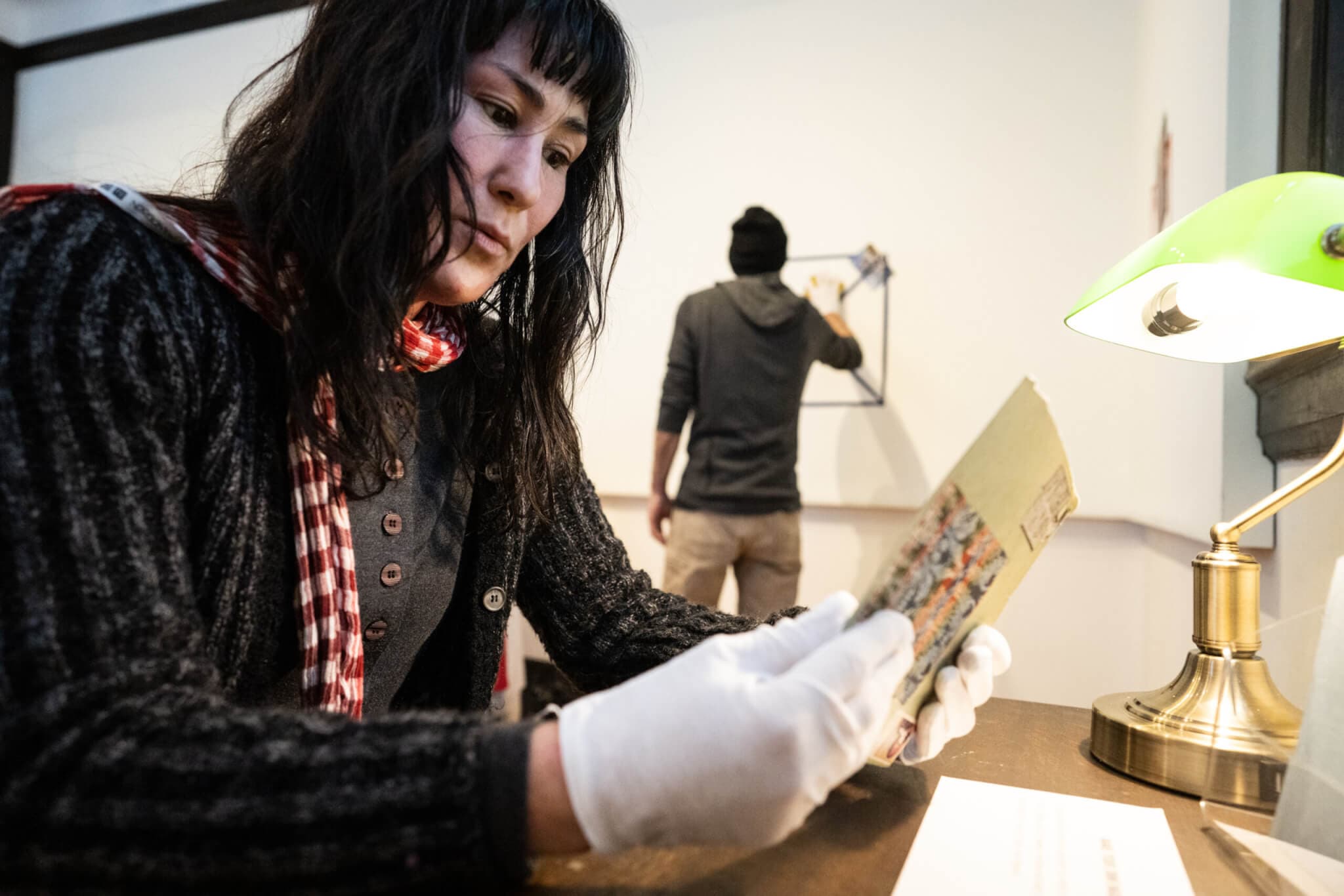

For her solo exhibition at the Brattleboro Museum & Art Center, Brooklyn-based artist and archivist Mitsuko Brooks’s epistles hang from wire or nestle in lattice-like ribbon arrangements suggestive of decorative bulletin boards or letter racks from another age. Tacks and pins hold the ribbons taut. A sign lets you know it’s OK to slide these hardbacked postcards out from behind the ribbon and off the wall to look at both sides, as long as you wear white gloves and return everything to where you found it.

The show’s title, “Letters Mingle Souls,” is a quotation from a seventeenth-century poem, “To Sir Henry Wotton,” by John Donne. The phrase appears on US stamps commemorating the foundations of the global postal system. One of those commemorative postage stamps features a painting by the famed hyperrealist John Peto, Old Time Letter Rack (1894) in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, which shows letters stashed in a rectangle of pinned-up pink strips. Donne, like Brooks, relied on letter writing to pursue spiritual connections. “To Sir Henry Wotton” laments the state of the world and attempts to put Donne and Wotton’s friendship on an intimate plane above ordinary life.

Brooks’s correspondence as art is melancholic, diaristic, and sincere. In mail art, as in music, there can be sad, haunting songs. Brooks’s body of work is full of letters that resonate like songs—such as Billie Eilish and her brother Finneas singing about selfimage and being there for each other in “everything i wanted,” 2019. They sing, “As long as I’m here, no one can hurt you.” Brooks’s self-soothing, warmtoned collage Mail to self postmarked 5/23/2020, includes an apology and statements on her hopes for herself: “My wish for you is to make peace with your violent childhood and re[ach] forgiveness to your [parents]. I am sorry your primary caregivers […] cannot care for you the way you wanted and needed. You are already on your way to heal, building back your self-esteem, being your own parent.”

The works on view here often appear to have been sent and then retrieved. They’re all about the same size—the smallest measuring roughly three by five inches, the largest roughly ten by twelve. Many feature Brooks’s handwritten capital letters in cursive and with curlicue serifs. These letterforms run edge to edge on cast-off book covers and on top of found images showing toy horses, trees, floral patterns, and the like. Brooks has shown similar works widely in solo and group exhibitions in California, New York, Pennsylvania, and Oregon. For When you feel alone, 2022, over an image of the heavily fortified main tower of Osaka Castle in Japan, the artist wrote the reminder “there are so many people around you that love you.” For Mail to self postmarked January 4, 2019, she wrote to her future self at age forty-seven about hoping the older Mitsuko was highly successful as an artist, still worked in a library, and had by then saved money, fixed her teeth, and found an antidepressant that “doesn’t make you gain weight and feel flat but allows you to really let go of social anxiety.”

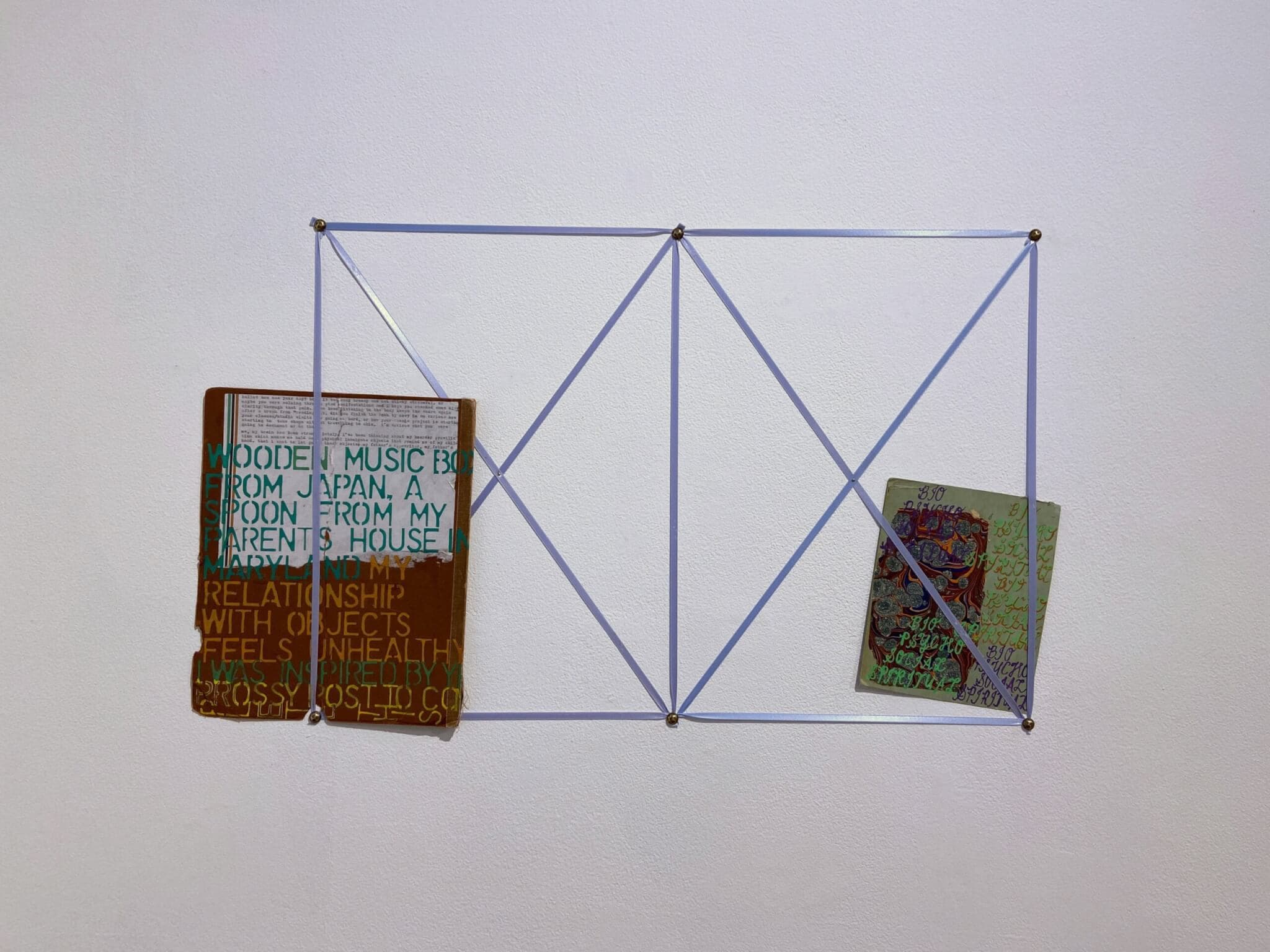

In another letter, Mail to Andrea Sisson postmarked Sept. 11, 2020, the artist asks questions as a check-in on her friend, then shares that she wants to loosen the unhealthy hold she feels objects have on her. This letter seems to have started as typewritten text on paper that Brooks then glued to a brown book cover. In the middle of the second paragraph, it appears she stopped typing and switched to stenciling letters, perhaps to highlight a couple of the items she was thinking of letting go: her father’s music box from Japan and a spoon from her parents’ house in Maryland. Brooks grew up with pen pals and has been writing letters as art for more than ten years. In the last year or so, she’s started making large-scale acrylic paintings on canvas that reproduce and enlarge one side of her earlier postcards, though none of these paintings are on view here.

In the gallery, there is a desk with a short stack of blue paper and a cup of markers and pens. Visitors will find the invitation “If you have lost someone and wish to write a note or letter to them, please use the paper provided and add your note to the installation by tucking it into the ribbons.” One note in the gallery the day I visited said, “You never gave up on me. I guess I wish you hadn’t given up on yourself.”

Next to this note, another work, Mail to Forrest Borie postmarked 2018, hangs like many of the others, within a rectangle of ribbon. A marbleized pattern on the former book cover consists of orange, crimson, and blue striations encircling what resemble geode-like gray bubbles. Brooks embedded in this surface a typed quote from Marie-Louise von Franz, a twentieth-century Jungian psychologist: “If one lived quite alone, it would be practically impossible to see one’s shadow because there would be no one to say how you looked from the outside. There needs to be an onlooker.”

Do there need to be onlookers and survivors? As part of a statement introducing the show, Brooks describes herself as someone who has lived with suicidal ideation and has experienced domestic violence. The show comes with a content warning issued by the museum. Suicide prevention resources are available on-site and online. In addition to writing to herself and friends, as a new endeavor for this show, Brooks worked with suicide-loss survivors to write to the person they lost. She engaged in this collaborative practice as a kind of writing beyond. The activity helped ground her. She wrote in her artist statement about her thought processes in creating this series—that if she could take in these messages developed for lost loved ones, perhaps she could handle her own suicidal ideation. To J.J., 2022, says, “Dear J.J., You’re A Good Person. I Love You.” To Danielle, 2022, says, “Sometimes it feels like you died yesterday as though if I tried hard enough, I could … hug you just once more.”

In an interview that accompanied a group exhibition at the Elizabeth Foundation for the Arts in Manhattan last year, Brooks described how she weaves art therapy into her work as an artist. “I cannot separate my personhood and my art practice,” she explained. Brooks and curator David Rios Ferreira contextualize the Brattleboro exhibition in its accompanying texts as a message of hope to suicide-loss survivors. Brooks wrote, “I have a lifelong focus on finding meaning in life and reason to live.”

Well off the beaten path for contemporary art viewing, the Brattleboro Museum & Art Center currently features six other shows, including solid, curated solo exhibitions and artist projects and a historical exhibition of Keith Haring’s subway drawings. Brooks’s exhibition may make the most sense in Vermont. Like a message in a bottle, the first iteration of mail art often aims romantically for a particular audience, over some distance— say, from Brooklyn to Brattleboro. Mail art is an effort to move between and connect, a letting out, and a letting go. It’s part of a conversation, a fragment that could always remain dangling—perhaps a whispery unanswered invitation, a wistful look back, or a stamped and postmarked yearning. In “Letters Mingle Souls,” mail art ventures beyond life and death. This feels appropriate. Vermont, with its small and proud population, shut-in winters, candles in windows, moose, and covered bridges, feels connected still to an earlier time.

A redbrick post office with gothic lamps is just a few blocks down from the museum. A spindly antique mail cart sits on display in the lobby. I watched a mail carrier leave from there and start on her route, dropping off envelopes and parcels at the various shadowy Victorian houses in town. Then I learned that the gallery where Brooks’s exhibition hangs used to be a ticket office before the museum came about. The museum building used to be a train station, taking passengers to and from other places and other worlds.

“Mitsuko Brooks: Letters Mingle Souls” is on view at the Brattleboro Museum & Art Center through June 11, 2023.

This piece was originally published in Issue 10: RECALL, our spring/summer 2023 issue. Order it here.

The print version of this article contains two phrases the artist requested to have redacted from online. (Updated June 10, 2023.)