Each summer, the BAR editors look a little farther afield to find the exhibitions that must make the summer “to-do” list. This year, with too many excellent shows dotting New England, we’re splitting the list in two with separate recommendations for museum and gallery shows.

We’re excited about exhibitions as far south as Layo Bright’s first museum show at The Aldrich in Ridgefield, Connecticut, to Anthony Cudahy’s solo presentation at the Ogunquit in Maine. Closer to home, two photography exhibitions by Boston-area artists arrive at the Athenaeum and Gardner and in North Adams we’re eagerly awaiting Steve Locke’s MASS MoCA homecoming.

Installation view: “Layo Bright: Dawn and Dusk”, The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, 2024. Photo by Jason Mandelia. Courtesy of the artist.

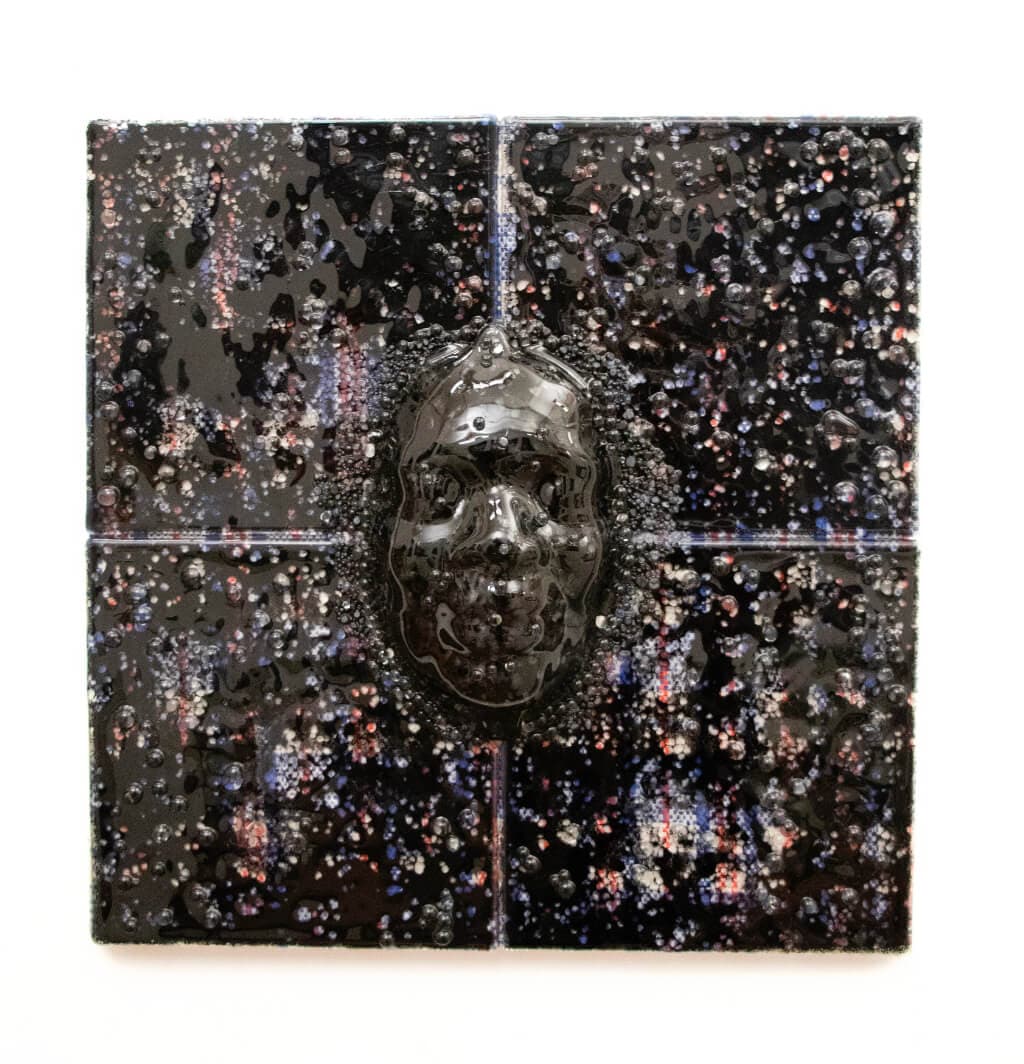

Layo Bright, Point of Last Scatter, 2020. Kiln formed glass, Ghana Must Go bag on wood frame, 20″ x 20″ x 3″. Photo by Layo Bright. Courtesy of Tariku Shiferaw.

“Layo Bright: Dawn and Dusk,” April 7–October 27, 2024

The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum

258 Main Street, Ridgefield, CT

Oscillating between figuration and abstraction, Layo Bright’s works in “Dawn and Dusk” demonstrate an astounding array of media—from ceramics to innovative glass techniques that push the medium to new meanings. As the show explores themes of matriarchy, migration, and her Nigerian upbringing and ancestry, it also presents tender portrayals of the Black women in Bright’s life: whether portraits of herself and her family, or homages to women such as Breonna Taylor, Sade, and other figures. The show is a feast for the senses—one gallery is filled with the sounds of water from a luminous, black glass fountain sculpture inspired by her grandmother’s hometown in Nigeria. With her first solo museum exhibition under her belt, Bright’s future is as luminous as her name.

—Gina Lindner

Installation view, “Anthony Cudahy: Spinneret,” Ogunquit Museum of American Art, Ogunquit, ME, 2024. Photo courtesy of Ogunquit Museum of American Art.

“Anthony Cudahy: Spinneret,” April 12–July 21, 2024

Ogunquit Museum of American Art

543 Shore Road, Ogunquit, ME

At the Ogunquit Museum of American Art, it’s hard to compete with the view. And yet Brooklyn-based painter Anthony Cudahy’s “Spinneret” manages it, wresting eyes away from the serene blue of Perkins Cove cradling the Atlantic to focus instead on the charged reds and electric yellows of Lily and mirror with Apocalypse Tapestry (2022) and Lily and snake bundle (“And she took the time to believe in what she said and”) (2021)—the two works that flank the gallery’s glass back wall. Contemporary art lovers may recognize the Lily portrayed in both pieces as fellow painter Lily Wong. She, along with the photographer Ian Lewandowski—Cudahy’s husband—peoples many of the paintings.

The more than thirty works on view are full of domestic intimacy. Yet close crops, angled planes, and surrealist elements—cobwebs that act as sun rays—veer the canvases away from familiar scenes into territories warped by layered references, from Queer archives to Derek Jarman films to allegorical and art historical motifs. The work is so rich and challenging (and frankly such a joy to look at) that it’s a shock to discover that it’s Cudahy’s first solo show in the United States. Thankfully, curator Devon Zimmerman provides a generous introduction, offering the (mostly) large works the space to breathe and glow, and thoughtfully annotating them with accompanying texts to highlight their dense networks of inspiration. Much like the webs the show is named after, the result is strong and delicate, intricate and cohesive, all at once.

—Jessica Shearer

C. Rose Smith (American, born in 1995), Untitled no. 000, 2020. Three-channel film. Courtesy the artist. © C. Rose Smith and Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Shanequa Gay (American, born in 1977), Video installation, 2:57 minutes. Courtesy the artist. © C. Rose Smith and Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

“Four Womxn: New Musings on Blackness,” May 11–November 18, 2024

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

465 Huntington Ave., Boston

The gaze is Black, queer, and multiple. The four artists in this show rework archetypal portrayals of Blackness and demand that we examine the structures that perpetuate them. C. Rose Smith’s three-channel video offers a sharp critique of respectability politics as it intersects with femininity and masculinity: Untitled no. 000 (2020) instrumentalizes an ostensibly simple white cotton dress shirt to ask, in Deleuzian fashion, what is actually encoded in such a garment. Querying the simultaneous presence and absence of Black women’s bodies, Le’Andra LeSeur’s White Out (2018) valiantly confronts exclusion within feminism. Illuminated on the wall, Porsha Olayiwola’s Twerk Villanelle (2019) poetically queers the performance of twerking. Shanequa Gay’s video installation The Crooked Room (2018) pairs stunning visuals with Melissa Harris-Perry’s characterization of experiencing the world as a Black woman. Be sure to relisten to Nina Simone’s “Four Women” before your visit to contextualize the intervention these artists are making.

—Alisa V. Prince

Kathia St. Hilaire, David, 2022. Reduction linocut in oil-based ink on canvas with tires, resin, banana leaves, fabric, metal, paper, rabbit skin glue, pigment, and thread, 9′ x 12′. Photo by Guillaume Ziccarelli. Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin.

“Kathia St. Hilaire: Invisible Empires,” May 11–September 22, 2024

Clark Art Institute

225 South St., Williamstown, MA

South Florida–raised, New York–based Haitian American artist Kathia St. Hilaire refers to her work as “magical realism.” It’s a term more commonly applied to fiction than visual art. Indeed one of the artist’s large mixed-media collages, David (2022), depicts the 1979 hurricane that devastated Haiti while referencing a similar storm depicted by the godfather of the literary movement, Gabriel García Márquez. And yet when gazing at the nearly twenty works on view in “Kathia St. Hilaire: Invisible Empires,” the artist’s solo show at the Clark Art Institute, one can immediately see how the phrase pertains.

What magical realism suggests is that by leaning into the murky and magnificent expanse of the unknowable—in recognizing how the inexplicable plays out in our histories and lived experiences—we in fact get quite a bit closer to that which we feel to be real. By patterning her pieces with up to fifty layers of linocut-printed ink and imbricating materials as varied and culturally loaded as skin-lightening cream, Chiquita banana stickers, and bank notes, St. Hilaire illuminates narratives that condemn the centuries of violence from invaders like France and the US, and celebrate the traditions that have enabled its people to survive. Her pieces are trenchant and turbulent—and in their willingness to stretch beyond the borders of historical uniformity—tell us a great deal about the world we actually live in.

—Jessica Shearer

Kristen Joy Emack, Spring, 2021. Inkjet print. Photo courtesy of the artist.

“Cousins,” May 13–August 26, 2024

Boston Athenaeum

10½ Beacon St., Boston

Kristen Joy Emack has been photographing her daughter and nieces for over a decade. Her black-and-white images capture the essence of the girls as they navigate the journey of growth, embracing moments of joy and fostering deep bonds with one another. Each frame—frozen representations of dynamic scenes—is a living time capsule. As her daughter and nieces have matured, they have become active collaborators in the project. Their voices craft intimate narratives through the exhibition labels, offering viewers an insight into the backstory behind the captured moment. “Cousins” is found in a quiet corner of the Boston Athenaeum. A selection of staff-recommended books, thoughtfully aligned with the themes explored in Emack’s photos, further enriches the experience, encouraging visitors to engage deeply with the imagery before them.

—Kaitlyn Ovett Clark

Photograph by Wendel A. White of Baby Dolls from the Kenneth and Mamie Clark collection, Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture; Gift of Kate Clark Harris in memory of her parents Kenneth and Mamie Clark, in cooperation with the Northside Center for Child Development Washington, DC. © Wendel White.

“Manifest: Thirteen Colonies,” May 18, 2024–April 13, 2025

Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnography

11 Divinity Ave., Cambridge

A shard of glass. A manuscript. Shackles—Wendel White photographs Black American material culture sourced from public and private collections within the first thirteen colonies of the United States. Images of objects such as Radcliffe anthropologist Caroline Bond Day’s family tree featuring photographs and hair samples are juxtaposed across the small cubical gallery with a lock of Frederick Douglass’s hair. The body of work collapses time and space across each piece of stimuli that White photographed by drawing attention to the infinite connections between and expansions beyond them. The result is a remarkable project that evokes both memory and wonder.

—Alisa V. Prince

Hew Locke, “The Procession,” Tate Britain Commission 2022. Installation view: “Hew Locke: The Procession,” Institute of Contemporary Art / Boston, 2024. Photo by Mel Taing. Courtesy the artist.

“Hew Locke: Procession,” May 23–Sep 2, 2024

Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston Watershed

256 Marginal St, Boston

Journeying from one edge of the Atlantic to another, “Hew Locke: The Procession” travels through the ICA Watershed on East Boston’s waterfront this summer after debuting at Tate Britain. Guyanese British sculptor and visual artist Hew Locke’s nearly 140 masked figures of various ages and abilities are propelled forward, their bodies often made of cardboard assemblage and patchworked cloth. They move for many reasons and in many places, resembling a protest, Carnival, military parade, funeral, or underground railroad. Their garments and props contain images of historical documents—including maps, banknotes, and photographs—that reverberate the legacy of colonization, imperialism, global trade, and empire. A small child wearing a global map holds a figurine-sized skeleton in a raft-like vessel. I got caught in the unwavering gaze of a front-facing figure whose head was rotated ninety degrees to the right. They are all going somewhere, and perhaps the miracle—or warning—is so can we.

—Niara Simone Hightower

Jeremy Frey, Loon, 2020. Ash, cedar bark, porcupine quill on birch bark, and dye, 36″ x 23″ x 23″. Private collection of Catherine Stiefel, California. © Jeremy Frey. Photo by Eric Stoner.

“Jeremy Frey: Woven,” May 24–September 15, 2024

Portland Museum of Art

7 Congress Sq., Portland, ME

Passamaquoddy artist Jeremy Frey has become one of the most awarded and collected Indigenous basket weavers in the country for his contemporary mastery of the Wabanaki weaving tradition. Intricately foraged and woven from fine strands of ash, cedar, and birch bark with porcupine quills and sweetgrass, the tradition has been stewarded for thousands of years by Northeast tribes—particularly the Passamaquoddy, Penobscot, Maliseet, and Mi’kmac. Frey, who originally learned from his mother, has been instrumental in innovating upon the ancient tradition and bringing the practice into the global contemporary art world. In 2023, the artist became represented by New York gallery Karma. His baskets take on sumptuous forms, sometimes resembling sea urchins or featuring embroidered imagery on the lids. At the Portland Museum of Art, the exhibition featuring more than fifty baskets is the first museum retrospective of a Wabanaki artist.

—Jameson Johnson

Michael Thorpe, camp atwood, 2021. Fabric, thread, and quilting cotton, 81.5″ x 63″. Collection of Jonathan Bush and Fay Rotenberg. Courtesy of Fuller Craft Museum.

“Michael C. Thorpe: Homeowners Insurance,” June 8–December 1, 2024

Fuller Craft Museum

455 Oak St., Brockton

Michael C. Thorpe was on the path to become a basketball star before shifting his focus while at Emerson College to focus on film and fine art. Now, at thirty-one, the New York-based artist is having his second solo museum exhibition featuring his quilted masterpieces at the Fuller Craft Museum in Brockton. Thorpe grew up around quilting, but his work is anything but traditional. He uses bold colors, textures, and stitching patterns to create abstract representations of everyday scenes from dance floors to portraits of political figures. Thorpe’s pieces are altogether familiar, abstract, and referential—if only we could crawl inside his quilted world.

—Jameson Johnson

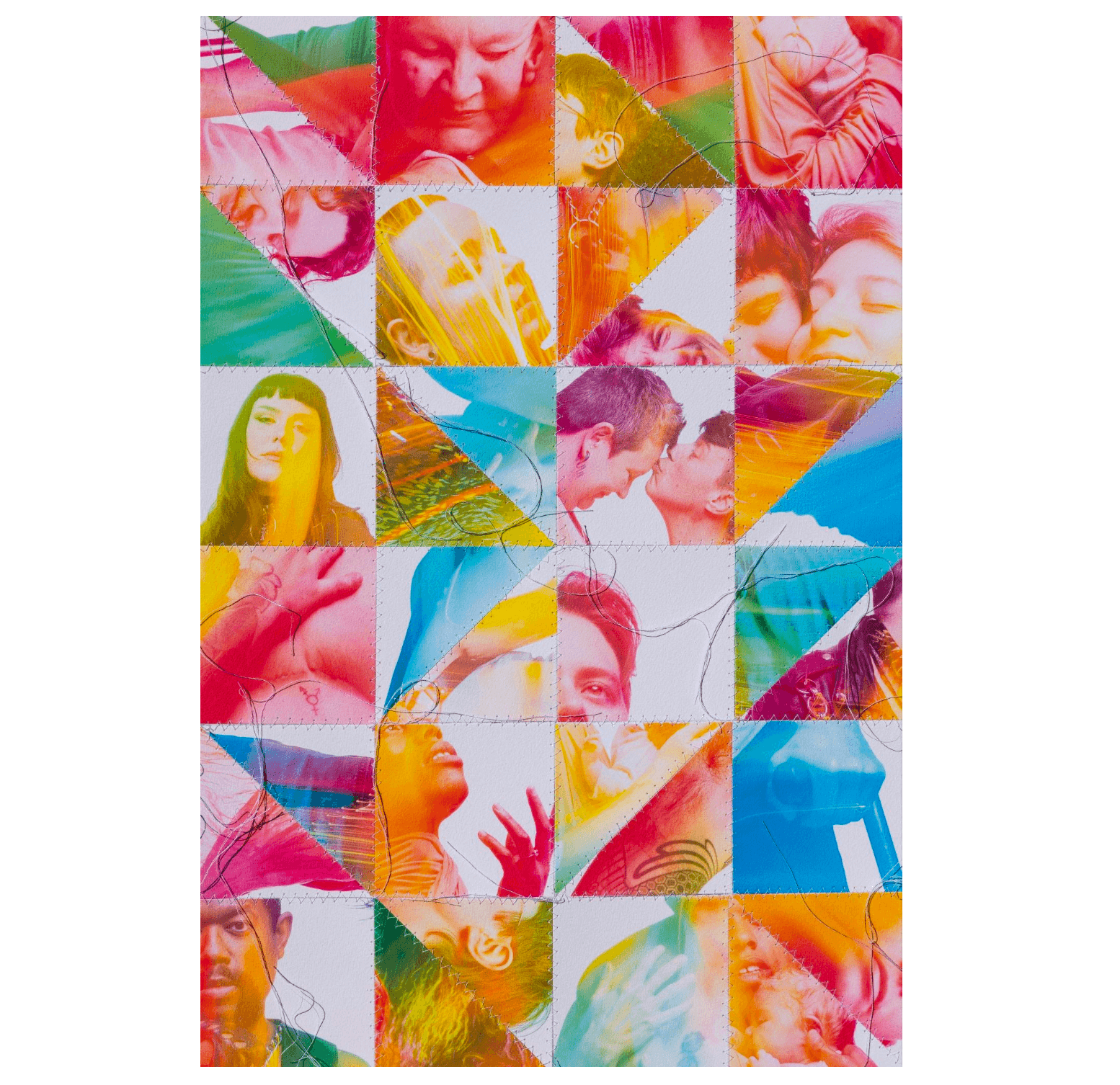

Ally Schmaling, Quilt 3, 2024. Inkjet print on mold-made watercolor paper, string, 19 ½” x 13”. Collection of the artist © 2024, all rights reserved Ally Schmaling.

“Portraits from Boston, With Love,” June 13–September 8, 2024

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum

25 Evans Way, Boston

The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum presents a summer exhibition suite of portrait photography from New York, Dallas, and Boston. Across three galleries and in partnership with The Theater Offensive—the Museum’s first Community Organization-in-Residence—the exhibition centers artists who use “photography as a tool to amplify queer, nonbinary, and trans visibility, beauty, survival, resistance, and community.”

Though the collections are singular in voice, each joins in the conversation. “On Christopher Street: Transgender Portraits by Mark Seliger” calls out across the Hostetter Gallery to Hakeem Adewumi’s “Possession of a Recalcitrant Dream” on the Anne H. Fitzpatrick Façade. From the Fenway Gallery, “Portraits From Boston, With Love” speaks back with its portrayal of the LGBTQIA+ experience from three artists who call Boston and its neighborhoods home. January 2024 Gardner Museum Artist-in-Residence Olivia Slaughter utilizes stark contrast and shadows to make portraits of chosen family. Jaypix Belmer (Jaypix) turns the camera on themself to create self-portraits washed with gold. Ally Schmaling experiments with light and bathes their subjects in a kaleidoscope of psychedelic colors. Visually stunning and aesthetically distinct, these works are odes to love—of community, of chosen family, and of oneself.

—Ava Mancing

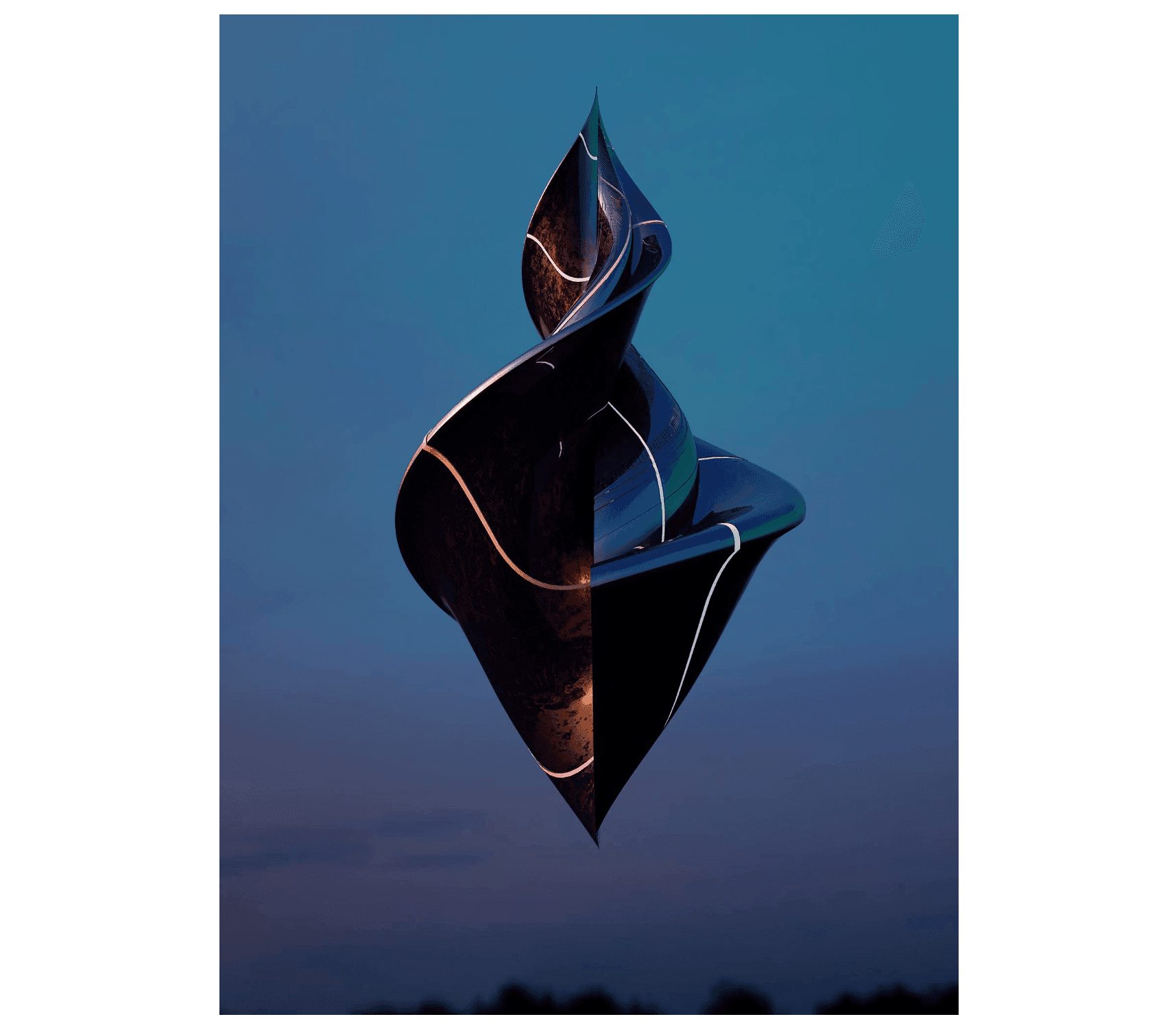

Saks Afridi, Sighting #6, 2019. Foam print, 46″ x 34″. Courtesy of Brattleboro Museum & Art Center.

“Saks Afridi: SpaceMosque,” June 22–October 19

Brattleboro Museum & Art Center

10 Vernon St., Brattleboro, VT

For his first solo museum exhibition in the United States, Saks Afridi lays bare the parafictional premise of his sci-fi Sufism “SpaceMosque” series of works: the average American viewer has few positive perceptions of contemporaneous practices of Islamic mysticism, much less its rich global histories and futures. “SpaceMosque” invites us to move beyond the sting of our provisional knowledge. Here, he is playing with Americans’ decades-long obsession with unidentified flying objects to speculate the possibility of airborne, atemporal prayer vessels through glossy aluminum prints and sculpted artifacts. Seeing might not yet be believing, but Afridi and his many collaborators certainly make the act plausible.

—Toby Wu

Maya Watanabe, Zhùr, 2024. Single-channel video installation, 18 minutes. Courtesy of the artist, tegenboschvanvreden, and 80m2 Livia Benavides.

“Displacement,” June 27–December 8, 2024

MassArt Art Museum

621 Huntington Ave., Boston

Nine artists explore humans’ relationship with the environment in this wide-ranging show curated by MAAM executive director Lisa Tung. It promises the premiere of Maya Watanabe’s video Zhùr, which trains a lens on a 57,000-year-old wolf pup preserved in permafrost—no longer permanent thanks to climate change—and the US debut of Sandra M. Sawatzky’s The Black Gold Tapestry, a two-hundred-foot hand-embroidered textile that traces humanity’s history with oil all the way back to boats built from bitumen in ancient Mesopotamia. Other intriguing offerings include Katie Paterson’s incense sticks evoking scents of the planet’s first and last forests, Nyugen E. Smith’s assemblages inspired by ad hoc homes constructed after crises, and Imani Jacqueline Brown’s installation connecting contemporary fossil fuel infrastructure with histories of slavery and colonialism in Louisiana. Coming to the museum through the Fenway area? Keep an eye out for Justin Brice’s solar-powered roadway signs, which trade traffic directives for pithy eco-aphorisms.

—Jacqueline Houton

Tomashi Jackson, Here at the Western World (Prof. Windham’s Early 1970’s Classroom & the 1972 Second Baptist Church Choir), 2023. Property of a Private Collection, Boston. Acrylic, Yule Mountain Quarry marble dust, and southern Colorado sand on paper bags, canvas, and textile with PVC marine vinyl, brass hooks, and grommets on a handcrafted wood awning structure. Photo courtesy of the artist and Tilton Gallery.

“Tomashi Jackson: Across the Universe,” July 30–December 8, 2024

Tufts University Art Galleries

Aidekman Arts Center

40 Talbot Ave., Medford

After stops in Denver and Philadelphia, Cambridge-based artist Tomashi Jackson’s “Across the Universe” comes home to Tufts University Art Galleries. Covering the development of Jackson’s practice over the last nine years, “Across the Universe” highlights the artist as storyteller as she reflects on the narratives she collected from communities of color across the US. Diving into the layered histories of social justice and resistance in the face of oppression, Jackson explores the complexity and nuance of these stories through a unique lens developed over years of practice—informed in part by her interest in color theory and the murals she grew up with in California. Through video, painting, prints, sculpture, and other media, “Across the Universe” merges Jackson’s exploration of inequity and activism across the United States with the power of aesthetics.

—Karolina Hać

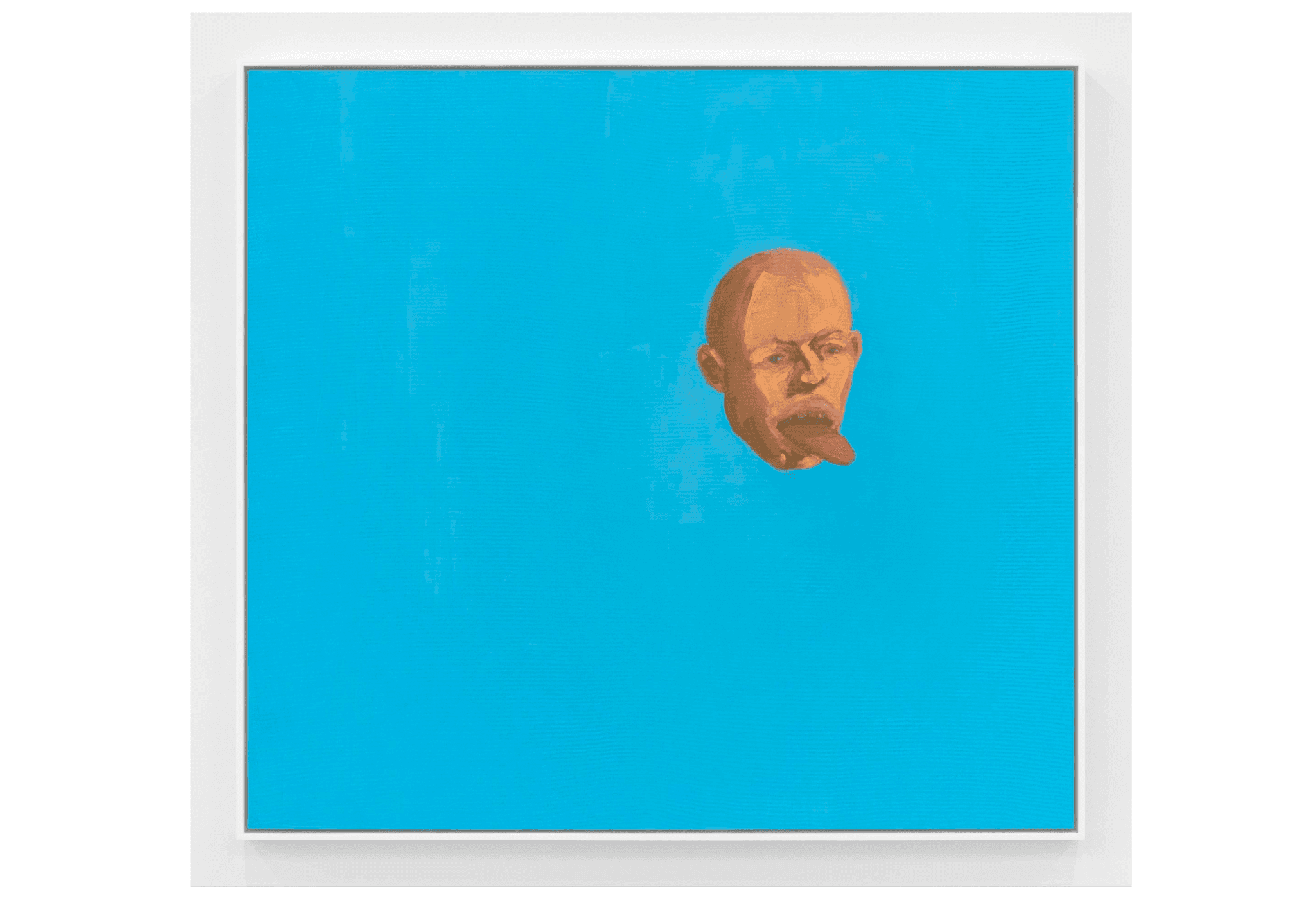

Steve Locke, the harbinger, 2022. Oil on canvas, 55” x 60” (56 ¼” x 61 ¼” x 2 ¼” framed). © 2024 Steve Locke / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

“Steve Locke: the fire next time,” August 3, 2024–TBD

Mass MoCA

1040 MASS MoCA Way, North Adams, MA

Steve Locke’s Mass MoCA exhibition marks a highly anticipated homecoming for the acclaimed artist and educator. Since his early days at MassArt, he has gone on to make major waves in both the local and international art community. Sharing its title with the James Baldwin book, “the fire next time” will tie a thread between Locke’s explorations of history and memory, portraiture and objecthood, while mining the histories of racism, anti-Blackness, and violence toward Black and queer people in America. The show will spotlight his most compelling series in painting and installation, plus a newly commissioned, site-specific sculptural installation and other new works. Much like Baldwin, Locke’s artistic voice has been a guiding light in tumultuous recent years, offering both hard truths and humor, and I’m excited to see what he’s cooking up.

—Gina Lindner